The history of the chess horse

Having evolved from the Indian game chaturaṅga around the sixth century, the thirty-two pieces and sixty-four squares have made their way to nearly every continent and culture in the intervening centuries.

In all countries, wherever chess appeared, the army included figures depicting a horse or a rider on a horse. In the ancient shatrang - ancient Persian chess, the figures were Indian warriors sitting on mighty horses. Many centuries ago, cavalry was the most important branch of the army. She could decide the outcome of any battle. And in chess, the knight can decide the outcome of the game.

In Europe it was accepted that a knight without a horse does not even have the right to be called a "cavalier". And they kind of merged into one whole. And therefore, in many countries in ancient times, chess figures fought, depicting a rider on a horse.

Chess Piece in the Form of a Knight, Date: ca. 1350–60, Metropolitan museum

Over time, the proud chess horse managed to get rid of the rider in all the chess states of the world, but the name “knight” remained.

The knight is colloquially sometimes referred to as a "horse", which is also the translation of the piece's name in several languages. Some languages refer to it as the "jumper", reflecting the knight's ability to move over pieces in its path: Polish skoczek, Danish/Norwegian springer, Swedish springare, German Springer, Luxembourgish Sprénger, Slovene skakač. In Sicilian it is called sceccu, a slang term for a donkey, derived from the Arabic sheikh, who during the Islamic period rode from village to village on donkeys collecting taxes.

In great works of literature and history, life has been metaphorically alluded to a game of chess. Indeed, life could easily be compared to an engaging game of chess, with each person having to deal with one’s own set of pawns, knights, kings or queens and applying the many strategies of the game in the art of planning, adapting to situations, problem solving and more.

"The Chess Players", Liberale da Verona, ca 1475, Metropolitan museum

Chess also is a great analogy for society, its limitations, and how each class of society interacts with each other. The Knight might not be the most powerful or the most willing to follow his leader around, but his skill set is unique and gets him the recognition needed to be used frequently. The Knights of society are the people who are really good at one and only one specific thing.

In Medieval times, chess grew in popularity across Europe. Brought by Islamic traders from India, where it was invented around 500 BC, the game was adapted to fit European societal structures. The game and its pieces served as a metaphor for the forces at work in a world that was hard to comprehend. Many lived lives filled with wars, disease, difficult work, and little agency. For them, the structure of the game and its pieces was a way to make sense of a chaotic world. The popularity of the game in Europe is a testament to a world with growing global connections, which were built through trade, like that between Norway and Scotland.

Although the number of Knights and Bishops on the chessboard is the same, more medieval chess pieces in the form of Knights survive. This example, perfectly poised on his fine horse, battles a dragon, a symbol of evil. But for the lack of a halo and a princess in need of rescue standing nearby, he might be mistaken for Saint George, who, according to legend, slayed a dragon.

Knight Chess Piece, Date: ca. 1250, Metropolitan museum

Perhaps the most famous and valuable chess set is the Lewis Chessmen hoard, found in 1831 in the far reaches of northern Scotland. They give us fascinating insights into the international connections of western Scotland and the growing popularity of chess in medieval Europe. Late 12th – early 13th century. The collection of fifty-nine ivory and whales' teeth pieces is believed to have been lost by a Norwegian tradesman in the late-twelfth to early-thirteenth century. In 2019, Sotheby's sold a single rediscovered piece from the hoard for nearly $1 million.

One knight, mounted on his horse, bearing a spear and a shield.

The style of the carving links the pieces to Norway – there is a similar chess piece from Trondheim, and the Lewis figures’ thrones are reminiscent of carving in medieval Norwegian churches. Most of the Lewis chess pieces are made from walrus ivory. This was probably obtained in Greenland and traded back to Norway.

Lewis chess pieces from the British Museum's collection

Another notable chess piece is the Charles Hollander Royal Diamond contemporary chess set that was created in some 4,500 hours by craftsmen painstakingly handcrafting each nuance of every individual piece. The 14-carat pieces are designed in white gold and embellished with 9,900 white and black diamonds weighing a total of around 186.09 carats.

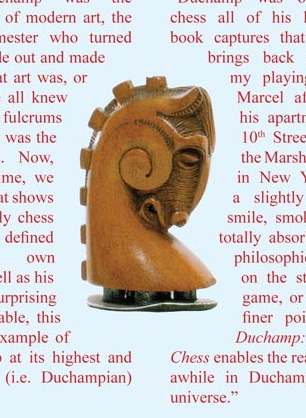

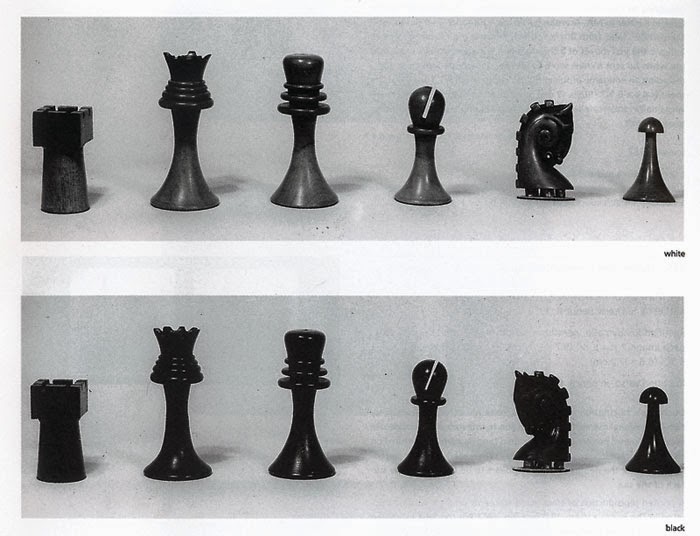

Marcel Duchamp's chess set. Though his influence 20th and 21st century art is hard to understate, the French artist Marcel Duchamp devoted more of his life to chess. Born into a family of keen amateur chess players, Duchamp played throughout his early adult life, while creating such works as Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, The Large Glass and Fountain.

By the early 1920s, he was no longer a practising artist, preferring instead to play the game. He was awarded the title of chess master by the French Chess Federation in 1925, joined the French Olympic team and played in a number of international tournaments during the 1920s and 30s.

Duchamp did, however, find ways to work art into his love of chess. He staged a number of chess-themed exhibitions, played chess with his friend Man Ray in the 1924 film Entr'act, and in 1968, performed a concert with John Cage, wherein sounds were triggered by photoelectric cells set into the pair’s chessboard. Around 1917 he created his own chess set, and went on to make chess-piece stamps to play chess via mail, and a portable set. Duchamp’s original set is not commercially available though 3D printing enthusiasts have tried to recreate the pieces.

References:

Metropolitan museum

National Museums Scotland

Wikipedia

Phaidon